visit social media pages for news on this week’s happenings

Click a button to jump directly to a Good News story below

visit social media pages for news on this week’s happenings

Click a button to jump directly to a Good News story below

Click to jump directly to a Good News story below

The Magic in Stories:

Back in 1990, I attended my first ArtVenture[1] with a group of 1st and 2nd graders from Banff Elementary School. Only dropping my fingers (five kids on each hand) to point out their paintings, the students told me about their lives, their world of knowledge, and the dreams they depicted in those paintings.

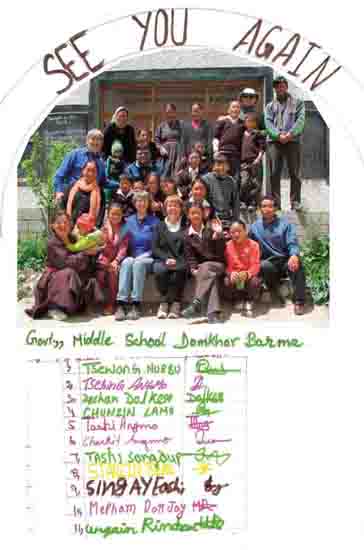

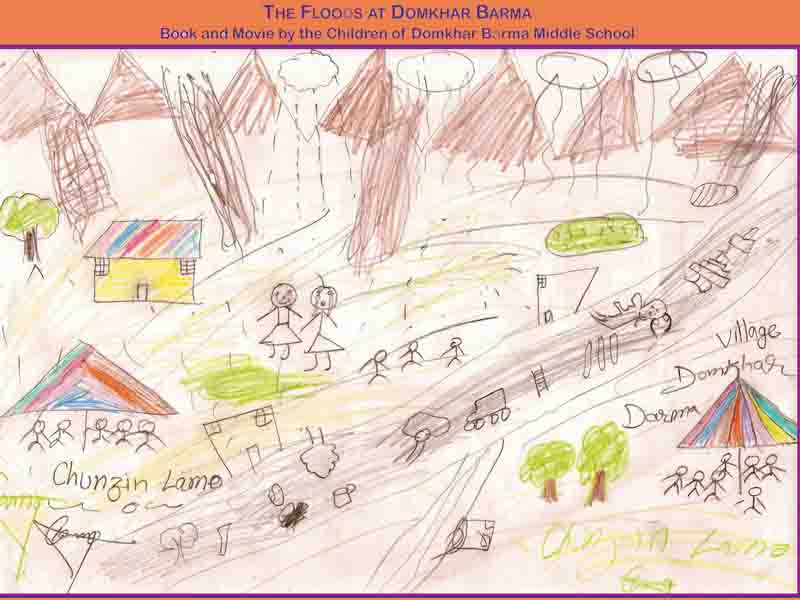

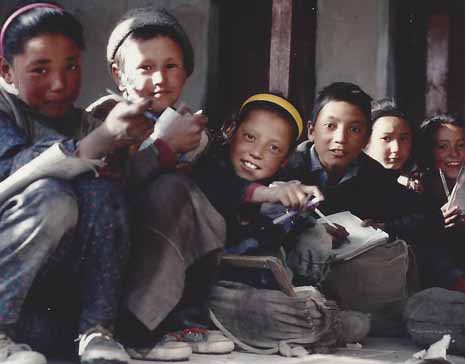

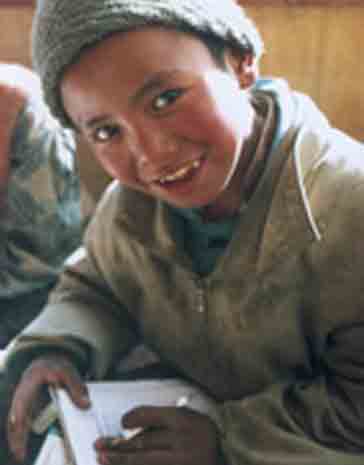

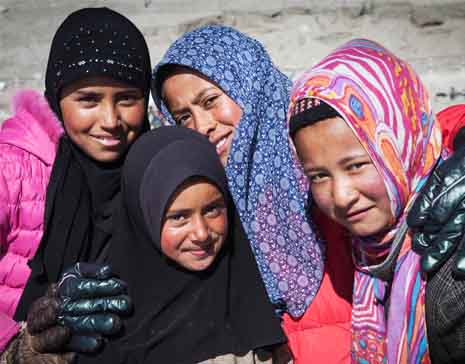

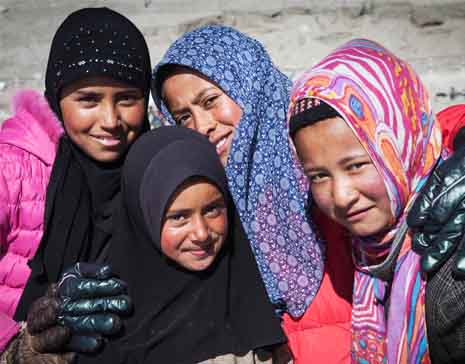

The same teachers who prompted my ArtVenture invitation arranged for classroom visits where I shared art and stories from the Tibetan refugee children with whom I worked in Ladakh, India[2]. These were magical learning times – for the Banff students, for me, and for the teachers, as children pondered other kids’ lives and dreams. I asked for a repeat visit each time I returned to North America.

[1] ArtVenture, a program showcasing local school children’s artwork supported by the City of Banff, the Banff Centre for the Arts, local businesses and the school district, celebrated young students’ artwork with a professionally displayed show and opening celebration for the entire community. (Later footnotes at the end of the story)

The Magic in Stories:

Back in 1990, I attended my first ArtVenture[1] with a group of 1st and 2nd graders from Banff Elementary School. Only dropping my fingers (five kids on each hand) to point out their paintings, the students told me about their lives, their world of knowledge, and the dreams they depicted in those paintings.

The same teachers who prompted my ArtVenture invitation arranged for classroom visits where I shared art and stories from the Tibetan refugee children with whom I worked in Ladakh, India[2]. These were magical learning times – for the Banff students, for me, and for the teachers, as children pondered other kids’ lives and dreams. I asked for a repeat visit each time I returned to North America.

[1] ArtVenture, a program showcasing local school children’s artwork supported by the City of Banff, the Banff Centre for the Arts, local businesses and the school district, celebrated young students’ artwork with a professionally displayed show and opening celebration for the entire community. (Later footnotes at the end of the story)

Title photo: the Story of Goat made by Ladakhi exchange youth. Above: Reading a Ladakhi book at the Banff Mountain Film Festival, Pre-internet exchanges from Ladakh, Answering questions in Alberta. Below: Children’s stories of their Canadian homes, Comparing India and Canada and a retired Canmore teacher in Ladakh.

Title photo: the Story of Goat made by Ladakhi exchange youth. Above: Reading a Ladakhi book at the Banff Mountain Film Festival, Pre-internet exchanges from Ladakh, Answering questions in Alberta. Below: Children’s stories of their Canadian homes, Comparing India and Canada and a retired Canmore teacher in Ladakh.

Over the years, kids came up with the most amazing ways to exchange experiences and a real relationship grew between the School District of the Canadian Rockies and village children and youth living in remote areas of another fantastic mountain range. Teachers visited us in Ladakh and sent classroom videos and letters. I returned the favor by bringing stories of snow leopards, science puzzles and skating on ponds at 11,500 feet to students in Canada.

During one enthusiastic visit back to Banff, I was introduced to a required-reading, social studies book on India – told through the voice of a Canadian girl traveling around India for several weeks. She describes the different people and places she sees – but it is a Canadian voice and perception that first introduces Albertans to India[3]. Teachers explained that the curricular goal was to make the world sound familiar. And yet, we all agreed that engagements through our little exchanges were more rewarding learning opportunities for all the kids.

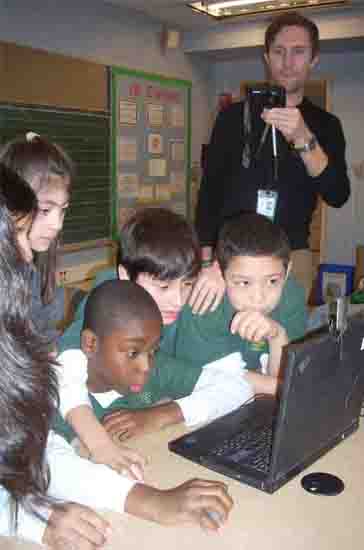

Above: One student representing the wealth of Canadian resources, Students flocking to the computer to talk to overseas friends, Below: 100 ways to communicate.

That day, the Global Classroom Initiative (GCI) was born. While the Initiative has always been informal, teachers on both sides of the Pacific recognized that supporting young people to share their similarities and differences was a natural means to spur meaningful questions and experiential learning that stuck. Third graders wanted to know how a country with elephants could also be home to the highest and youngest mountains in the world, and Ladakhi children queried how the second largest country in the world could be home to less than 35 million people. Stories were the richest way to learn, allowing children to use their imagination – and a few reference books – to build accurate pictures of the world around them.

Luck intervened – or maybe some of our own story telling, and in 2001, I was introduced to Pat and Baiba Morrow, videographer/storytellers extraordinaire looking for their next adventure. They found it in the Initiative, and if you wanted to grow a program, you could do worse than partnering with the first Canadian summiting the seven tallest mountains on the seven continents, and a couple so very capable of taking complex stories and weaving a cinematographic journey.

Over two years of filming, we made sure kids were able to share ideas and ask important questions – like the value of community, what defines Albertans, or Ladakhis, and what unites eight year olds no matter where they live. These elementary students asked deep questions after sharing their favorite foods, or the responsibility of caring for a pet rabbit or a newborn lamb.

Above: 1 student representing the wealth of Canadian resources, Students flocking to the computer to talk to overseas friends, Below: 100 ways to communicate.

That day, the Global Classroom Initiative (GCI) was born. While the Initiative has always been informal, teachers on both sides of the Pacific recognized that supporting young people to share their similarities and differences was a natural means to spur meaningful questions and experiential learning that stuck. Third graders wanted to know how a country with elephants could also be home to the highest and youngest mountains in the world, and Ladakhi children queried how the second largest country in the world could be home to less than 35 million people. Stories were the richest way to learn, allowing children to use their imagination – and a few reference books – to build accurate pictures of the world around them.

Luck intervened – or maybe some of our own story telling, and in 2001, I was introduced to Pat and Baiba Morrow, videographer/storytellers extraordinaire looking for their next adventure. They found it in the Initiative, and if you wanted to grow a program, you could do worse than partnering with the first Canadian summiting the seven tallest mountains on the seven continents, and a couple so very capable of taking complex stories and weaving a cinematographic journey.

Over two years of filming, we made sure kids were able to share ideas and ask important questions – like the value of community, what defines Albertans, or Ladakhis, and what unites eight year olds no matter where they live. These elementary students asked deep questions after sharing their favorite foods, or the responsibility of caring for a pet rabbit or a newborn lamb.

Pat and Baiba’s documentary, “The Magic Mountain”, was entered into the 2005 Banff Mountain Film Festival, It featured two young Ladakhis: a health worker and a young man whose dream was teaching. Serendipity triumphed yet again and the local Albertan Rotary Club created a six-week storytelling exchange and invited the Ladakhi youth to Canada. Norboo shared children’s health challenges while Stanzin was introduced to experiential learning for the first time. What an opportunity for these youth to share their lives, their knowledge and their dreams with Canadians!

One day as students ate lunch with Stanzin, several distraught kids dragged me off to the classroom explaining “Miss, Miss, Stanzin is very upset, but we didn’t do anything. Honest.” Soliciting a bit of information, indeed, he was upset. ”How could children have so little respect for the blessing of good food – taking one bite of a sandwich or apple and throwing the rest out?”

Norboo explained that in Ladakh food is sacred – so is water, soil and life itself. How could these eager, inquisitive, well-educated young people not know and believe this? Their parents must work awfully hard to afford and pack these nice lunches day after day. A trash can? And what happens to the food after that? Not even feeding leftovers to your cow, who gives milk, or your sheep, who gives wool?

Left: Food is sacred. Baiba and Pat Morrow on the trail. Below: The Magic Mountain, Stanzin and Norboo at work, Cynthia with teachers in Banff. Bottom Row: Excited exchange participants and Canmore Rotarians.

Pat and Baiba’s documentary, “The Magic Mountain”, was entered into the 2005 Banff Mountain Film Festival, It featured two young Ladakhis: a health worker and a young man whose dream was teaching. Serendipity triumphed yet again and the local Albertan Rotary Club created a six-week storytelling exchange and invited the Ladakhi youth to Canada. Norboo shared children’s health challenges while Stanzin was introduced to experiential learning for the first time. What an opportunity for these youth to share their lives, their knowledge and their dreams with Canadians!

One day as students ate lunch with Stanzin, several distraught kids dragged me off to the classroom explaining “Miss, Miss, Stanzin is very upset, but we didn’t do anything. Honest.” Soliciting a bit of information, indeed, he was upset. ”How could children have so little respect for the blessing of good food – taking one bite of a sandwich or apple and throwing the rest out?”

Norboo explained that in Ladakh food is sacred – so is water, soil and life itself. How could these eager, inquisitive, well-educated young people not know and believe this? Their parents must work awfully hard to afford and pack these nice lunches day after day. A trash can? And what happens to the food after that? Not even feeding leftovers to your cow, who gives milk, or your sheep, who gives wool?

Left: Food is sacred. Baiba and Pat Morrow on the trail. Below: The Magic Mountain, Stanzin and Norboo at work, Cynthia with teachers in Banff. Bottom Row: Excited exchange participants and Canmore Rotarians.

Above: What do we really need? Below set of 8, Left to Right: Ladakh exchanges with the American Embassy School and a trip over the Rockies, Canadian youth in Ladakh and classroom chats via Skype, Teacher exchanges and Videos produced together, Changes for youth on both continents and time to reflect on us and them.

My soul sings when learning moments like these appear – and the more we share ideas across differences, the more music is made. That incident sparked a class’s month-long learning unit exploring food waste in the classroom, then the school, the province and the world. They explored the relationship between Albertan farmers and the consumers who eat their food, and parents struggling to afford healthy food for the children they feed. Science was pulled in by actually composting and digging into nutritional facts. Math joined next with weighing waste, food budgets and how much farmers earned from the cost of a loaf of bread. And language arts took flight as children traveled to and filmed stories of the cultural importance of grain elevators disappearing across the Albertan landscape. Teachers were supported by the Galileo Educational Network, an incredible University of Calgary’s School of Education initiative. Kids reduced food waste, created budgets and learned history from cowboys, farmers and elevator operators –experiential ways for them to think about being responsible consumers of earth’s resources. Music. Magic!

We built opportunities for Canadian youth to have their own GCI experience in remote Ladakh-based winter camps, after sharing time with Ladakhi counterparts in their high school, sports program or community. One Canadian participant had always defined himself by a dream of playing pro hockey, and felt lost when that dream wasn’t realized. Spending time in Ladakh, he learned how skilled he was at helping others look deep into themselves, and that maybe his career would be more meaningful in helping young Canadians expand their own personal goals. A young woman with a real lack of self-confidence discovered that young people flocked to her empathetic capacity and that self-doubt had no business making a home in her heart or mind.

A teacher in the Banff School described it to me as students’ lives were becoming a lot of “good enough, gotta go” and “I didn’t get any likes this weekend”. With too many supervised activities, with too much social media and with less time for interdisciplinary, open-ended learning, today’s students simply lacked opportunities to discover concepts for themselves and grow as a community. We saw it in Ladakh, too, and several of our young leaders questioned how their projects could support deep questioning and across-differences programs. How could they shift away from chasing “likes” or unimaginative career dreams of social influencing and develop the courage to talk about the pressing issues in their lives? And maybe even learn that these issues of isolation, social justice and building healthy change are universal?

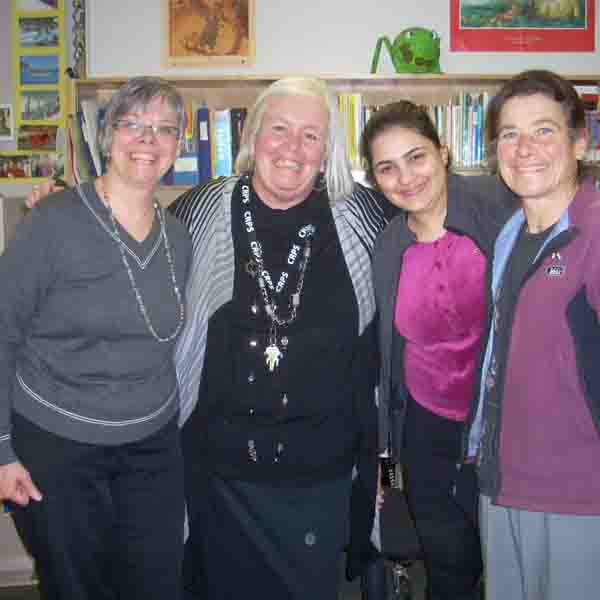

In November 2023, we participated in one final GCI with a new partner in Winnipeg, a much beloved, older partner-school in Montreal and a Montreal-based NGO that supports young people traveling to war-torn or dislocated communities around the world[5].

Padma and Gurmet came with me to experience teaching mental wellness in classrooms and mentoring kids on the ice hockey rink in Winnipeg. They got to think long and deep about the importance of being there for students as they ponder big questions in their lives and getting down to kid’s eye level to let them know this is a safe relationship in which to be inquisitive. They saw the classroom structure needed for high schoolers to challenge themselves and take time to try, try and try again – and then apply problem solving to local issues of importance in their futures. There were peer-to-peer discussions on the emotional impacts of over-scheduled lives (and “good enough, gotta go”) and social media pressures. And time – for Canadians and Ladakhi alike – to reflect on how nice it is to not feel alone in questions about self, or social justice, or the future. And wide-open spaces to simply skate together, eat together, listen to music together; and experience the power of listening across divides.

This, our last project, got back to the basics of storytelling and sharing across differences, from a young man questioning food waste to time spent sharing lives, knowledge and dreams. Magic.

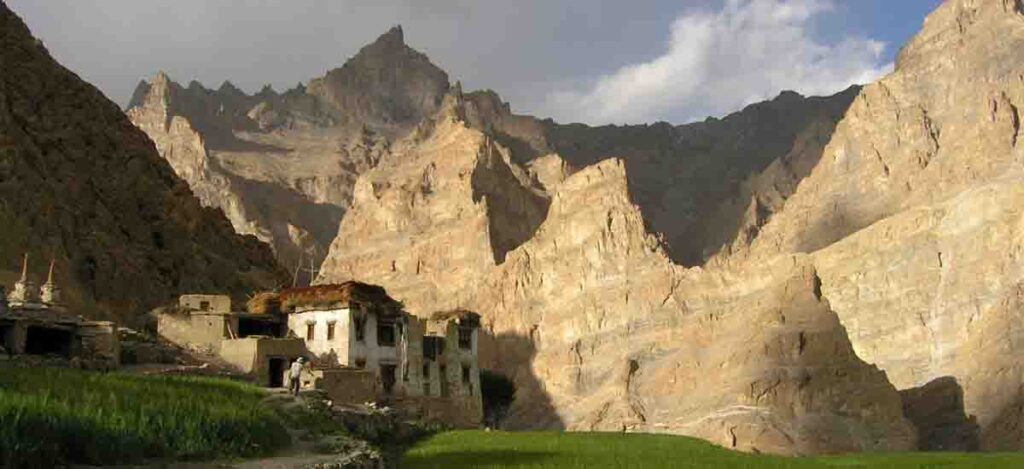

[2] Ladakh Union Territory lies in the northwest Himalayas of India, with peaks reaching over 23,000 feet / 7000 metres and most of the valleys are over 9500 feet / 3000 metres.

[3] The rest of the social studies series used indigenous voices for each geographic location (Newfoundlanders for a St John’s fishing story, a Greenlander describing herding reindeer, and Albertan farmers for their home province). I didn’t understand why India was told in a Canadian voice.

[4] After more than 20 years of engagement with classrooms across North America and communities in the Himalayas, the HELP inc Fund is dissolving its 501 (c) (3) non-profit and turning its remaining funds over to Omprakash, a like-minded US charity, to carry work forward.

[5] The True North Youth Foundation in Winnipeg, Lower Canada College in Montreal and Hockey sans Frontiers.

Photographs courtesy of Pat and Baiba Morrow, Mary Schearer, Nicole Lundstead, HEALTH Inc staff, the Academy for Global Citizenship, the American Embassy School, True North Youth Foundation and Lower Canada College.

Padma Rigzin (right) carries the Global Classroom Initiative forward through his work with HEALTH Inc Ladakh and the Omprakash Foundation.

Cynthia Hunt retired from over thirty years of work in Ladakh this past December. The HELP Fund closed its doors to make room for other, younger charities to lead the way in spring 2024.

Padma Rigzin (right) carries the Global Classroom Initiative forward through his work with HEALTH Inc Ladakh and the Omprakash Foundation.

[2] Ladakh Union Territory lies in the northwest Himalayas of India, with peaks reaching over 23,000 feet / 7000 metres and most of the valleys are over 9500 feet / 3000 metres.

[3] The rest of the social studies series used indigenous voices for each geographic location (Newfoundlanders for a St John’s fishing story, a Greenlander describing herding reindeer, and Albertan farmers for their home province). I didn’t understand why India was told in a Canadian voice.

[4] After more than 20 years of engagement with classrooms across North America and communities in the Himalayas, the HELP inc Fund is dissolving its 501 (c) (3) non-profit and turning its remaining funds over to Omprakash, a like-minded US charity, to carry work forward.

[5] The True North Youth Foundation in Winnipeg, Lower Canada College in Montreal and Hockey sans Frontiers.

Photographs courtesy of Pat and Baiba Morrow, Mary Schearer, Nicole Lundstead, HEALTH Inc staff, the Academy for Global Citizenship, the American Embassy School, True North Youth Foundation and Lower Canada College.

Cynthia Hunt retired from over thirty years of work in Ladakh this past December. The HELP Fund closed its doors to make room for other, younger charities to lead the way.

Try Doing More Good than Harm

“Why don’t you spend the rest of your life trying to do more good than harm?”

People often ask me how I ended up working in the Western Himalayas for more than 30 years. There’s the 30 seconds or less answer of “I came for the mountains and stayed for the people,” and there is the longer answer prompted by a meeting in 1992 with His Holiness the Dalai Lama where the question of doing more good than harm arose.

“Why don’t you spend the rest of your life trying to do more good than harm?”

People often ask me how I ended up working in the Western Himalayas for more than 30 years. There’s the 30 seconds or less answer of “I came for the mountains and stayed for the people,” and there is the longer answer prompted by a meeting in 1992 with His Holiness the Dalai Lama where the question of doing more good than harm arose.

Try Doing More Good than Harm

“Why don’t you spend the rest of your life trying to do more good than harm?”

People often ask me how I ended up working in the Western Himalayas for more than 30 years. There’s the 30 seconds or less answer of “I came for the mountains and stayed for the people,” and there is the longer answer prompted by a meeting in 1992 with His Holiness the Dalai Lama where the question of doing more good than harm arose.

Try Doing More Good than Harm

“Why don’t you spend the rest of your life trying to do more good than harm?”

People often ask me how I ended up working in the Western Himalayas for more than 30 years. There’s the 30 seconds or less answer of “I came for the mountains and stayed for the people,” and there is the longer answer prompted by a meeting in 1992 with His Holiness the Dalai Lama where the question of doing more good than harm arose.

I had an extremely typical Midwest, small-town upbringing; maybe not Leave it to Beaver, but 1960s solid. When I was 21, I walked from Mexico to Canada along the Continental Divide in the U.S. Rockies, doing the first 2,400 miles alone. Being early in recovery, I wanted to see the mountains, and I wanted to challenge myself physically, mentally and emotionally. For the last 800 miles, I had a partner, Ellen; a teacher by profession who had just returned from 14 months travelling around the world. She was filled with stories of people and places I could hardly imagine, and encouraged me to try it too. After all, hadn’t I decided to walk for six months in the western mountains?

Cynthia, age 3, with her Mum’s sunglasses on upside down.

Cynthia and Ellen crossing into Canada on the Divide

Eight hundred miles. That’s a lot of days of walking and talking together. And slowly I began to think, “Well, why not?” I hitchhiked to Alaska, worked multiple jobs for six months, got a visa for Nepal, and Ellen and I were off for the Himalayas within a year.

After months of enjoying the beauty – or I could say of playing in other people’s backyards – I started appreciating the richness of the people, their culture and their way of engaging with life. I volunteered on a UN FAO [1] pest control project where parakeets were decimating ripe grain fields and leaving harvests hurting.

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization

Everest from the north side, 1983.

A water container on the Tibetan Plateau

I walked with Tibetan refugees from central Nepal to Kathmandu, where they hopped a bus to Bodhgaya, attending teachings of His Holiness, and listened to their stories of “fields on the hoof [2]”. With village women, I pondered affordable methods of feral dog-proofing chicken houses. When Tibet first opened to independent travelers, I landed there, and balanced time between mountains and dairy herd work. Never really excelling at book learning, I thrived on seeing the ingenuity of simple solutions people designed when pressed.

Imagine. A job – a career – where I could continually learn, grow, take and give back. Ellen reminded me, “Why not?” When Tibet shut down, I was asked to apply my experiences to “developing” infrastructure for Tibetan Refugees living in Ladakh, India. I found two wonderful university programs[3] that encouraged me to keep working while getting degrees – allowing me to experience the magical impact of blending authentic problem-solving a la traditional Himalayan knowledge with introducing new ideas or concepts.

My “job” did not pay enough for a fancy car, a fancier house or even lots of dinners out. But I gained so much more, and every time I felt pressured to return to North America and “settle down” I landed in a new situation filled with challenges and rich learning opportunities. I couldn’t bear to turn my back on that.

My growing skills in implementing grassroots development led to a job offer using appropriate technology in support of Tibetan Refugee farming communities elsewhere in India. While I missed the Himalayas, I got to see, and learn from mistakes made, in the “Industrial Development Complex,” where wise use of scarce resources was not the mantra. Rather it was “come in on budget, on time, and don’t worry about downstream impacts”. Indeed, in one project, a dispute arose when project funds invested in providing door-to-door tap water for one community would negatively impact the pool of funds available for providing neighbourhood-based water access for the entire valley. Some people would be better off in convenience, while others would lose out on a basic for human right – access to safe drinking water.

[2] Farmers have land – or fields. Herders have animals. When a herder refers to their wealth of ownership, they say their “fields have hoofs” meaning they don’t own the pastureland as much as they own the animals and their products.

[3] The University of Minnesota allowed me to blend the College of Agriculture with a Geography major in the College of Liberal Arts as a “returning student” (woman over 30 years of age with interesting life experiences). At the University of British Columbia, I was in an interdisciplinary Master of Science program blending planning, agriculture and geography with a thesis evaluating development in the Western Himalayas.

Everest from the north side, 1983.

A water container on the Tibetan Plateau

Students in a remote school 1989

Tibetan refugees breaking rocks 1989

I walked with Tibetan refugees from central Nepal to Kathmandu, where they hopped a bus to Bodhgaya, attending teachings of His Holiness, and listened to their stories of “fields on the hoof [2]”. With village women, I pondered affordable methods of feral dog-proofing chicken houses. When Tibet first opened to independent travelers, I landed there, and balanced time between mountains and dairy herd work. Never really excelling at book learning, I thrived on seeing the ingenuity of simple solutions people designed when pressed.

Imagine. A job – a career – where I could continually learn, grow, take and give back. Ellen reminded me, “Why not?” When Tibet shut down, I was asked to apply my experiences to “developing” infrastructure for Tibetan Refugees living in Ladakh, India. I found two wonderful university programs[3] that encouraged me to keep working while getting degrees – allowing me to experience the magical impact of blending authentic problem-solving a la traditional Himalayan knowledge with introducing new ideas or concepts.

My “job” did not pay enough for a fancy car, a fancier house or even lots of dinners out. But I gained so much more, and every time I felt pressured to return to North America and “settle down” I landed in a new situation filled with challenges and rich learning opportunities. I couldn’t bear to turn my back on that.

My growing skills in implementing grassroots development led to a job offer using appropriate technology in support of Tibetan Refugee farming communities elsewhere in India. While I missed the Himalayas, I got to see, and learn from mistakes made, in the “Industrial Development Complex,” where wise use of scarce resources was not the mantra. Rather it was “come in on budget, on time, and don’t worry about downstream impacts”. Indeed, in one project, a dispute arose when project funds invested in providing door-to-door tap water for one community would negatively impact the pool of funds available for providing neighbourhood-based water access for the entire valley. Some people would be better off in convenience, while others would lose out on a basic for human right – access to safe drinking water.

[2] Farmers have land – or fields. Herders have animals. When a herder refers to their wealth of ownership, they say their “fields have hoofs” meaning they don’t own the pastureland as much as they own the animals and their products.

[3] The University of Minnesota allowed me to blend the College of Agriculture with a Geography major in the College of Liberal Arts as a “returning student” (woman over 30 years of age with interesting life experiences). At the University of British Columbia, I was in an interdisciplinary Master of Science program blending planning, agriculture and geography with a thesis evaluating development in the Western Himalayas.

Former nomads, now breaking rocks. A mani/prayer wall. Complex geography.

Walking to villages 2004

With the Chief Agriculture Officer in a remote area

Welcomed in schools by the kids

You might think the answer is obvious. It was not – and is not to this day. Here, serendipity intervened. His Holiness the Dalai Lama was the patron of the organization operating the project in question and I suggested taking the disagreement to him, seeking his wise counsel. Everyone – including His Holiness – agreed, and we explained the situation to him. He was silent for some moments. And then he said, “You Westerners mean well with your aid [development money]. Sometimes you do more harm than good. Why don’t you spend the rest of your life trying to do more good than harm?”

Those were his opening thoughts on the subject. There was much more discussion, but those three sentences were imprinted in my brain immediately; my heart, my soul, my hands, my everything, from that moment on. It’s a very simple but very profound statement. Quite often as we go through life, we mean to do “good”. But we’re just reacting to life from our own perspective or needs. We’re not responding thoughtfully to a situation. In order to respond – or pause, and not respond – takes a much more thoughtful, deliberate approach.

You might think the answer is obvious. It was not – and is not to this day. Here, serendipity intervened. His Holiness the Dalai Lama was the patron of the organization operating the project in question and I suggested taking the disagreement to him, seeking his wise counsel. Everyone – including His Holiness – agreed, and we explained the situation to him. He was silent for some moments. And then he said, “You Westerners mean well with your aid [development money]. Sometimes you do more harm than good. Why don’t you spend the rest of your life trying to do more good than harm?”

Those were his opening thoughts on the subject. There was much more discussion, but those three sentences were imprinted in my brain immediately; my heart, my soul, my hands, my everything, from that moment on. It’s a very simple but very profound statement. Quite often as we go through life, we mean to do “good”. But we’re just reacting to life from our own perspective or needs. We’re not responding thoughtfully to a situation. In order to respond – or pause, and not respond – takes a much more thoughtful, deliberate approach.

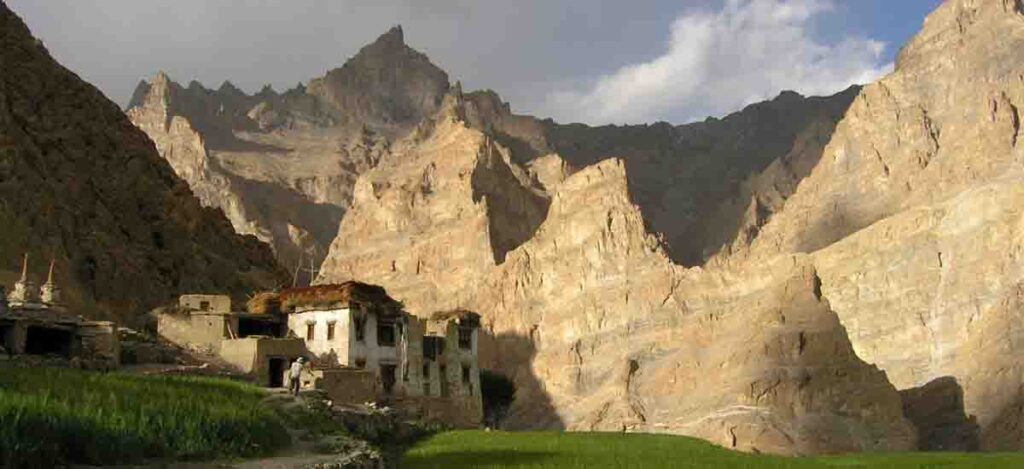

So, the next day, I quit that job and returned to Ladakh, to those beautiful mountains and the fascinating traditions they helped create. Co-workers and I had already founded a small NGO [4] in the Tibetan Community there, providing outreach to the remote communities whose land they shared. I collected a small amount of money, hired two young Ladakhis from extremely remote areas who craved a different learning experience (and who wanted to save up to go “outside” for studies) and we traveled to roadless villages asking people to paint us a picture of what a healthy future looked like to them – to themselves, their families, their communities and to Ladakh. HEALTH Inc (Health, Environment and Literacy in the Himalayas in Cooperation with Local People) was born. Over a year of long days’ walking, unhappy donkeys carrying loads and high mountain passes with brilliant blue skies above, traveling to a circuit of a dozen or so villages where other agencies didn’t go (“It’s too remote – no road goes there,” was the most common excuse I heard. Puzzling. Isn’t that exactly where careful thought of “development” should take place?), we held tightly to a philosophy of “doing more good than harm.”

And by “we” I mean that HEALTH Inc solicited input, membership and a board from renowned scholars to dedicated physicians – to expert, illiterate farmers. Youth were represented, as were teachers, taxi drivers and translators. The conch shell became our logo – one of the eight holy symbols in Buddhism, and also an ancient symbol calling people for learning and proclaiming truth as ideas are shared. Just defining “good” inspired a lot of thought in communities and groups who asked us to come work with them. Timelines were redrawn as consensus was important. Goals included having women representatives from every household in the village feeling comfortable with the balance between tradition and change – discussion and action – taking the risks they all were taking as a part of the “development “process.

[4] Non-Governmental Organization – organizations who fundamental aim is social but are not associated with any government. This particular work was with two Tibetans and two Ladakhis who I had been working with in several road-less villages in southern Ladakh.

So, the next day, I quit that job and returned to Ladakh, to those beautiful mountains and the fascinating traditions they helped create. Co-workers and I had already founded a small NGO [4] in the Tibetan Community there, providing outreach to the remote communities whose land they shared. I collected a small amount of money, hired two young Ladakhis from extremely remote areas who craved a different learning experience (and who wanted to save up to go “outside” for studies) and we traveled to roadless villages asking people to paint us a picture of what a healthy future looked like to them – to themselves, their families, their communities and to Ladakh. HEALTH Inc (Health, Environment and Literacy in the Himalayas in Cooperation with Local People) was born. Over a year of long days’ walking, unhappy donkeys carrying loads and high mountain passes with brilliant blue skies above, traveling to a circuit of a dozen or so villages where other agencies didn’t go (“It’s too remote – no road goes there,” was the most common excuse I heard. Puzzling. Isn’t that exactly where careful thought of “development” should take place?), we held tightly to a philosophy of “doing more good than harm.”

And by “we” I mean that HEALTH Inc solicited input, membership and a board from renowned scholars to dedicated physicians – to expert, illiterate farmers. Youth were represented, as were teachers, taxi drivers and translators. The conch shell became our logo – one of the eight holy symbols in Buddhism, and also an ancient symbol calling people for learning and proclaiming truth as ideas are shared. Just defining “good” inspired a lot of thought in communities and groups who asked us to come work with them. Timelines were redrawn as consensus was important. Goals included having women representatives from every household in the village feeling comfortable with the balance between tradition and change – discussion and action – taking the risks they all were taking as a part of the “development “process.

[4] Non-Governmental Organization – organizations who fundamental aim is social but are not associated with any government. This particular work was with two Tibetans and two Ladakhis who I had been working with in several road-less villages in southern Ladakh.

Walking the frozen Zanskar. An all-women’s meeting. The challenge of remote work.

“Good” to our founding President, Konchok Phanday, a Buddhist monk and a language scholar, meant every child had a right to learn in their mother tongue. Yet with the greater access to information, some felt there was a risk of a “disrespect for traditions” developing in youth. “Good” to our agricultural expert, a remote village woman with a wealth of knowledge and vision, was teaching young people to farm, to maintain the health of the land and protect the precious water resources. But “good” to our teacher meant children might need to leave the village and move to good education so their options were broader in the future.

Doing Good feels good – and for darned good evolutionary reasons. But it is also easy to become addicted to doing good, to “fixing it” for others. Our instant high has the cost of not letting others participate in the decision, and of imposing our concept of good on them. There is also the very human instinct of wanting what my neighbor has – especially if it a government program subsidized to the hilt. That’s great sometimes (universal access to immunizations) and doing harm at other times (monoculture tree plantations on high desert lands taking water away from native plant species).

“Good” to our founding President, Konchok Phanday, a Buddhist monk and a language scholar, meant every child had a right to learn in their mother tongue. Yet with the greater access to information, some felt there was a risk of a “disrespect for traditions” developing in youth. “Good” to our agricultural expert, a remote village woman with a wealth of knowledge and vision, was teaching young people to farm, to maintain the health of the land and protect the precious water resources. But “good” to our teacher meant children might need to leave the village and move to good education so their options were broader in the future.

Doing Good feels good – and for darned good evolutionary reasons. But it is also easy to become addicted to doing good, to “fixing it” for others. Our instant high has the cost of not letting others participate in the decision, and of imposing our concept of good on them. There is also the very human instinct of wanting what my neighbor has – especially if it a government program subsidized to the hilt. That’s great sometimes (universal access to immunizations) and doing harm at other times (monoculture tree plantations on high desert lands taking water away from native plant species).

I get the concept of disruption – but healthy change demands that support systems change too. When we build greater access to formal education, investment in bringing authentic learning into those institutions – and ensuring neighborhood access to quality schools is equally important. Some villages we worked with chose to invest heavily in winter (their out-of-school holidays) education programs that focus on learning about herding, farming, and water and land management. Programs that emphasize the joy of holidays spent together cooking, eating, singing and dancing. Young people have the opportunity to grow up with a love of community, leading them to respect much of it and make adaptations where needed to ensure survival of it for their own children. And they will be advocates for bringing that quality of learning into locally-based schools in the future.

Building that concept of joyful winters – in cooperation with village people – grew into our Winter Camp program: when focusing on experiencing community, a whole lot of other learning happens. It’s not just a nice side effect but the essence of our philosophy, slowly nurtured all these years.

Could I spend the rest of my life trying to do more good than harm? And what does that look like? I’ve dedicated my days, weeks and years to answering that question, to growing and changing and learning from experiences, from those who I’ve walked the road with; in this very rich, life. Thanks, Ellen. I mean – why not? After all, I’m a prairies girl in my soul with a lifelong love affair with mountains – and their people – in my heart.

I get the concept of disruption – but healthy change demands that support systems change too. When we build greater access to formal education, investment in bringing authentic learning into those institutions – and ensuring neighborhood access to quality schools is equally important. Some villages we worked with chose to invest heavily in winter (their out-of-school holidays) education programs that focus on learning about herding, farming, and water and land management. Programs that emphasize the joy of holidays spent together cooking, eating, singing and dancing. Young people have the opportunity to grow up with a love of community, leading them to respect much of it and make adaptations where needed to ensure survival of it for their own children. And they will be advocates for bringing that quality of learning into locally-based schools in the future.

Building that concept of joyful winters – in cooperation with village people – grew into our Winter Camp program: when focusing on experiencing community, a whole lot of other learning happens. It’s not just a nice side effect but the essence of our philosophy, slowly nurtured all these years.

Could I spend the rest of my life trying to do more good than harm? And what does that look like? I’ve dedicated my days, weeks and years to answering that question, to growing and changing and learning from experiences, from those who I’ve walked the road with; in this very rich, life. Thanks, Ellen. I mean – why not? After all, I’m a prairies girl in my soul with a lifelong love affair with mountains – and their people – in my heart.

I get the concept of disruption – but healthy change demands that support systems change too. When we build greater access to formal education, investment in bringing authentic learning into those institutions – and ensuring neighborhood access to quality schools is equally important. Some villages we worked with chose to invest heavily in winter (their out-of-school holidays) education programs that focus on learning about herding, farming, and water and land management. Programs that emphasize the joy of holidays spent together cooking, eating, singing and dancing. Young people have the opportunity to grow up with a love of community, leading them to respect much of it and make adaptations where needed to ensure survival of it for their own children. And they will be advocates for bringing that quality of learning into locally-based schools in the future.

Building that concept of joyful winters – in cooperation with village people – grew into our Winter Camp program: when focusing on experiencing community, a whole lot of other learning happens. It’s not just a nice side effect but the essence of our philosophy, slowly nurtured all these years.

Could I spend the rest of my life trying to do more good than harm? And what does that look like? I’ve dedicated my days, weeks and years to answering that question, to growing and changing and learning from experiences, from those who I’ve walked the road with; in this very rich, life. Thanks, Ellen. I mean – why not? After all, I’m a prairies girl in my soul with a lifelong love affair with mountains – and their people – in my heart.

In a Pandemic World

Revamping programs, responding to stated needs, the nuts and bolts of information access. Sometimes what people feel about service provision is more important than the services themselves.

In a Pandemic World

Revamping programs, responding to stated needs, the nuts and bolts of information access. Sometimes what people feel about service provision is more important than the services themselves.

In a Pandemic World

Revamping programs, responding to stated needs, the nuts and bolts of information access. Sometimes what people feel about service provision is more important than the services themselves.

In a Pandemic World

Revamping programs, responding to stated needs, the nuts and bolts of information access. Sometimes what people feel about service provision is more important than the services themselves.

In a Pandemic World

Revamping programs, responding to stated needs, the nuts and bolts of information access. Sometimes what people feel about service provision is more important than the services themselves.

“Who do you feel is helping you during this pandemic?” we asked a group of school-aged children and youth in a remote Ladakhi village in October of 2021. They replied with a blank stare. They looked at each other. “This must be a trick question,” read their expressions. They felt forgotten.

That was the experience for hundreds of young people in areas we serve in Eastern Ladakh. The reality was that the local administration and government agencies actually did an excellent job of keeping villages safe and deaths low. Large scale lockdowns banned social gatherings, closed schools, cancelled celebrations and allowed villages to ban outsiders from entering their valleys. Even vehicular traffic was regulated. Local health clinics commandeered buildings for COVID isolation and provided for all the needs of positive patients or those traveling home from “outside.” Food, bedding, utensils, even wash basins and access to safe water were all provided, for free.

“Who do you feel is helping you during this pandemic?” we asked a group of school-aged children and youth in a remote Ladakhi village in October of 2021. They replied with a blank stare. They looked at each other. “This must be a trick question,” read their expressions. They felt forgotten.

That was the experience for hundreds of young people in areas we serve in Eastern Ladakh. The reality was that the local administration and government agencies actually did an excellent job of keeping villages safe and deaths low. Large scale lockdowns banned social gatherings, closed schools, cancelled celebrations and allowed villages to ban outsiders from entering their valleys. Even vehicular traffic was regulated. Local health clinics commandeered buildings for COVID isolation and provided for all the needs of positive patients or those traveling home from “outside.” Food, bedding, utensils, even wash basins and access to safe water were all provided, for free.

“Who do you feel is helping you during this pandemic?” we asked a group of school-aged children and youth in a remote Ladakhi village in October of 2021. They replied with a blank stare. They looked at each other. “This must be a trick question,” read their expressions. They felt forgotten.

That was the experience for hundreds of young people in areas we serve in Eastern Ladakh. The reality was that the local administration and government agencies actually did an excellent job of keeping villages safe and deaths low. Large scale lockdowns banned social gatherings, closed schools, cancelled celebrations and allowed villages to ban outsiders from entering their valleys. Even vehicular traffic was regulated. Local health clinics commandeered buildings for COVID isolation and provided for all the needs of positive patients or those traveling home from “outside.” Food, bedding, utensils, even wash basins and access to safe water were all provided, for free.

So why, in survey after survey, did kids tell us that “no one is helping us”?

While Ladakh succeeded brilliantly in keeping the pandemic at bay, we failed at providing ways to universally access information, socialize safely, establish new routines making people feel like contributors, and, especially, for students – all students – to access education.

Don’t get me wrong. People with generous access to the internet could find information on COVID 19 – from protocols, to causes and ways to stay safe –and their children had access to private school teachers and lessons via their mobiles. Those with money played online games together, video chatted, and socialized in a new way.

Meanwhile, thousands of Ladakhis, as well as the migrant labourers from other parts of the sub-continent who sheltered in Ladakh during the first two years of lockdowns, could not. They were let down – and not just by government, which realistically, faced an insurmountable challenge. NGOs gave money to the government despite knowing it lacked sufficient capacity to use it well. Or they focused on physical needs (Enough! with the hand washing contraptions and competing over procuring and distributing oxygen tanks) at the expense of social needs.

None of us – not government, social services, NGOs or the private sector – addressed the isolation challenge. Whether it was remote villagers without access to the internet, or poorer people who couldn’t afford access, or elderly without a way to socialize safely, or youth wanting to contribute to a new normal, none of us knew what to do – so we didn’t try. In those dark places, misinformation thrived, resentment grew, and hope withered

So why, in survey after survey, did kids tell us that “no one is helping us”?

While Ladakh succeeded brilliantly in keeping the pandemic at bay, we failed at providing ways to universally access information, socialize safely, establish new routines making people feel like contributors, and, especially, for students – all students – to access education.

Don’t get me wrong. People with generous access to the internet could find information on COVID 19 – from protocols, to causes and ways to stay safe –and their children had access to private school teachers and lessons via their mobiles. Those with money played online games together, video chatted, and socialized in a new way.

Meanwhile, thousands of Ladakhis, as well as the migrant labourers from other parts of the sub-continent who sheltered in Ladakh during the first two years of lockdowns, could not. They were let down – and not just by government, which realistically, faced an insurmountable challenge. NGOs gave money to the government despite knowing it lacked sufficient capacity to use it well. Or they focused on physical needs (Enough! with the hand washing contraptions and competing over procuring and distributing oxygen tanks) at the expense of social needs.

None of us – not government, social services, NGOs or the private sector – addressed the isolation challenge. Whether it was remote villagers without access to the internet, or poorer people who couldn’t afford access, or elderly without a way to socialize safely, or youth wanting to contribute to a new normal, none of us knew what to do – so we didn’t try. In those dark places, misinformation thrived, resentment grew, and hope withered

HEALTH Inc loves stepping into such spaces. Could we create something providing hope to these people on the wrong side of the digital divide? In the first twenty-one days of the pandemic when “lockdown” meant no one was allowed outside their houses without a “front line worker permit,” we offered Karuna during Corona – Caring during Corona. Volunteers produced 21 activities engaging the heart and mind in simple tasks. A renowned local chef shared traditional recipes to make with grandma. Health experts and HEALTH Inc members created kid-friendly, fun lessons about the virus and how to stay safe. Artists shared tips on photography, encouraging kids to practice on mobile cameras from their roofs. Tailors taught folks to sew masks (back when we believed cloth masks were sufficient protection). Contests with prizes (free data!), and the small-file videos used low bandwidth apps as well as a Karuna Facebook page. We experimented with providing the videos offline in Internet-in-a-Boxes (IIABs) – devices able to broadcast in villages without internet access. This modest project taught us to work together and think outside the box (pun intended).

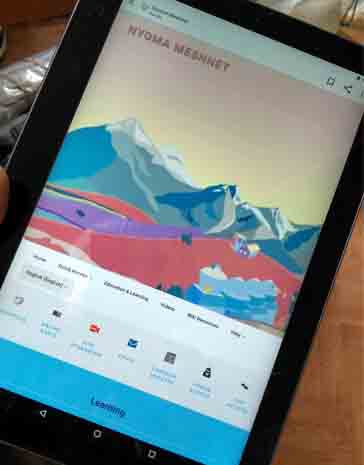

Yet from our first trip out to remote areas, armed with special front-line permits, eleven unemployed youth, activities, and IIABs, people told us they felt forgotten. We thought, ”Surely, in 2020, with all that technology and enthusiastic youth can do, we can address this digital divide and the mental health disaster it’s creating.” And that’s how HEALTH Inc’s MeshNet came into being.

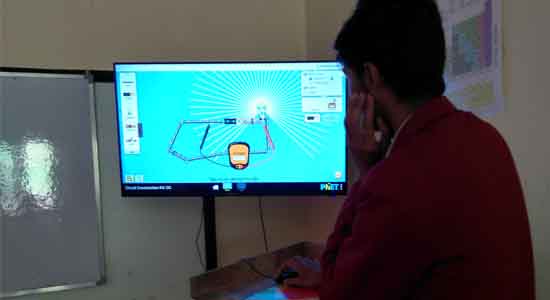

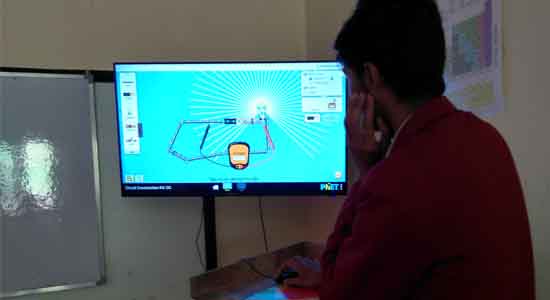

A “Meshnet” is simply a community of devices set up to share files. If IIABs can broadcast to a single room, we figured there must be a way to broadcast to a village. “Of course,” said the coding community we found through KIWIX, Wikimedia Foundation, MIT professors and bored coders in Bangalore who wanted to help address the lack of accurate information and the isolation. Simply put, we coded small servers with open source software, attached antennae for broadcasting signals and access points for receiving them, and uploaded whole varieties of information we thought useful. Health Department COVID Myth Busters, the entire state and national education syllabi, Khan Academy, Wikipedia in English and Hindi, PhET and Ted-Ed games and videos, and a few Ladakhi language lessons. A system and signal reaching up to 2.5 kilometres and 100 houses, where anyone could pull up anything 24/7 – no SIM card or tower needed – cost less than $1500.

HEALTH Inc loves stepping into such spaces. Could we create something providing hope to these people on the wrong side of the digital divide? In the first twenty-one days of the pandemic when “lockdown” meant no one was allowed outside their houses without a “front line worker permit,” we offered Karuna during Corona – Caring during Corona. Volunteers produced 21 activities engaging the heart and mind in simple tasks. A renowned local chef shared traditional recipes to make with grandma. Health experts and HEALTH Inc members created kid-friendly, fun lessons about the virus and how to stay safe. Artists shared tips on photography, encouraging kids to practice on mobile cameras from their roofs. Tailors taught folks to sew masks (back when we believed cloth masks were sufficient protection). Contests with prizes (free data!), and the small-file videos used low bandwidth apps as well as a Karuna Facebook page. We experimented with providing the videos offline in Internet-in-a-Boxes (IIABs) – devices able to broadcast in villages without internet access. This modest project taught us to work together and think outside the box (pun intended).

Yet from our first trip out to remote areas, armed with special front-line permits, eleven unemployed youth, activities, and IIABs, people told us they felt forgotten. We thought, ”Surely, in 2020, with all that technology and enthusiastic youth can do, we can address this digital divide and the mental health disaster it’s creating.” And that’s how HEALTH Inc’s MeshNet came into being.

A “Meshnet” is simply a community of devices set up to share files. If IIABs can broadcast to a single room, we figured there must be a way to broadcast to a village. “Of course,” said the coding community we found through KIWIX, Wikimedia Foundation, MIT professors and bored coders in Bangalore who wanted to help address the lack of accurate information and the isolation. Simply put, we coded small servers with open source software, attached antennae for broadcasting signals and access points for receiving them, and uploaded whole varieties of information we thought useful. Health Department COVID Myth Busters, the entire state and national education syllabi, Khan Academy, Wikipedia in English and Hindi, PhET and Ted-Ed games and videos, and a few Ladakhi language lessons. A system and signal reaching up to 2.5 kilometres and 100 houses, where anyone could pull up anything 24/7 – no SIM card or tower needed – cost less than $1500.

In remote villages, kids loved them. The games were fun, the health lessons valuable, and the movies a break from uncertainty. PhET physics simulations were far less stressful than memorizing a textbook, the usual method of learning. Villages established an offline phone and email system. There was a channel for government teachers to upload lessons and another for kids to upload their homework, so the annual school goals could at least be addressed if not met.

Our computer genius, Gurmet, worked with an international GitHub group fixing the bugs in AzuraCast – an open-source, offline community radio program. In 2022, success! Kids programmed a daily radio show, broadcasting to the school campus or the entire village. News, weather, a local interview, COVID updates and a science lesson or two could all go out over the airwaves and be accessed on any laptop, tablet or mobile phone. Students could Go Live! from a religious ceremony and video cast to vulnerable persons at home. Tower-less villages could experience the same benefits as people in the capital city.

We installed a total of five village MeshNets during three years’ of COVID closures and trained government schoolteachers to video and upload lessons, dramas and games. We searched for funding for other NGOs and youth groups to make additional local language materials and we kept traveling to remote areas and (safely) spent time with vulnerable groups. We pulled analytics from the servers and surveyed users on even more creative ways to lessen stress and dismantle those dark misinformation silos.

In remote villages, kids loved them. The games were fun, the health lessons valuable, and the movies a break from uncertainty. PhET physics simulations were far less stressful than memorizing a textbook, the usual method of learning. Villages established an offline phone and email system. There was a channel for government teachers to upload lessons and another for kids to upload their homework, so the annual school goals could at least be addressed if not met.

Our computer genius, Gurmet, worked with an international GitHub group fixing the bugs in AzuraCast – an open-source, offline community radio program. In 2022, success! Kids programmed a daily radio show, broadcasting to the school campus or the entire village. News, weather, a local interview, COVID updates and a science lesson or two could all go out over the airwaves and be accessed on any laptop, tablet or mobile phone. Students could Go Live! from a religious ceremony and video cast to vulnerable persons at home. Tower-less villages could experience the same benefits as people in the capital city.

We installed a total of five village MeshNets during three years’ of COVID closures and trained government schoolteachers to video and upload lessons, dramas and games. We searched for funding for other NGOs and youth groups to make additional local language materials and we kept traveling to remote areas and (safely) spent time with vulnerable groups. We pulled analytics from the servers and surveyed users on even more creative ways to lessen stress and dismantle those dark misinformation silos.

But to be honest, kids still felt forgotten, and hundreds lost two years of education, with many unable to catch up and complete their studies as lockdown protocols eased. Documented youth stress levels continued to rise and remain high today. A mistrust of local institutions taken for granted before 2020, was born.

And just like all those hand washing stations, the technology of the MeshNets worked. (We at HEALTH Inc remain strong believers in it as a means to bridge the digital divide.) Yet once the glamour of the games faded, people told us the most meaningful part of our work was simply visiting and acknowledging them. Our team liked the camaraderie of tackling challenges together. Teachers longed for less emphasis on exams and more time spent checking in with students, while building their skills of hybrid teaching. Youth craved a safe space to discuss how they felt.

So here are three lessons learned from our three years of providing universal access to information in a time of high levels of anxiety and disruption (because we believe there will be more times of unknowns and anxiety and disruption in the future):

But to be honest, kids still felt forgotten, and hundreds lost two years of education, with many unable to catch up and complete their studies as lockdown protocols eased. Documented youth stress levels continued to rise and remain high today. A mistrust of local institutions taken for granted before 2020, was born.

And just like all those hand washing stations, the technology of the MeshNets worked. (We at HEALTH Inc remain strong believers in it as a means to bridge the digital divide.) Yet once the glamour of the games faded, people told us the most meaningful part of our work was simply visiting and acknowledging them. Our team liked the camaraderie of tackling challenges together. Teachers longed for less emphasis on exams and more time spent checking in with students, while building their skills of hybrid teaching. Youth craved a safe space to discuss how they felt.

So here are three lessons learned from our three years of providing universal access to information in a time of high levels of anxiety and disruption (because we believe there will be more times of unknowns and anxiety and disruption in the future):

Build technology that can work today, not tomorrow. Construct simple open-source systems connecting people to accurate information while helping students build income-generating skills no matter their future education path. The technology needs to allow institutions to link villages to information regardless of location or household income. And NGOs and Agencies need to support their team of designers, people confident enough to build systems quickly. Invest in both now, not when the next catastrophe strikes.

Promote cooperation between service providers, not competition, especially in times when funding falls as it did during COVID. Working across organizations we could have delivered so much more. For example, the National Centre for Educational Research and Training (NCERT) has wonderful audio recordings of all their Indian national curricular books, but we lacked permission to offer them offline even though they are available on the NCERT YouTube Channel. We couldn’t raise money allowing other NGOs to spend lockdown time creating a wide variety of local-language learning materials. Networking is not just about the technology, but how we learn to work together.

Foster wellness and building resilience today to prepare for the next disruption. This may be more important than the hard skills because it opens spaces where we can talk about feeling uncertain or threatened and pulls in helpers willing and able to lead those conversations. Feeling uncertain doesn’t foster a climate of undertaking risky projects– from coding that might not work, to communicating openly, or pushing agencies to question their policies and work together for greater goals.

I love the simple village MeshNets we built and the joy seen in kids as they created their own broadcasts for remote villages during COVID isolation. The technology provided affordable, flexible services in remote areas and can do so again in the future, empowering young people to connect, cooperate and contribute. And feel like a part of a local solution; something that someone else’s solution cannot provide.

Build technology that can work today, not tomorrow. Construct simple open-source systems connecting people to accurate information while helping students build income-generating skills no matter their future education path. The technology needs to allow institutions to link villages to information regardless of location or household income. And NGOs and Agencies need to support their team of designers, people confident enough to build systems quickly. Invest in both now, not when the next catastrophe strikes.

Promote cooperation between service providers, not competition, especially in times when funding falls as it did during COVID. Working across organizations we could have delivered so much more. For example, the National Centre for Educational Research and Training (NCERT) has wonderful audio recordings of all their Indian national curricular books, but we lacked permission to offer them offline even though they are available on the NCERT YouTube Channel. We couldn’t raise money allowing other NGOs to spend lockdown time creating a wide variety of local-language learning materials. Networking is not just about the technology, but how we learn to work together.

Foster wellness and building resilience today to prepare for the next disruption. This may be more important than the hard skills because it opens spaces where we can talk about feeling uncertain or threatened and pulls in helpers willing and able to lead those conversations. Feeling uncertain doesn’t foster a climate of undertaking risky projects– from coding that might not work, to communicating openly, or pushing agencies to question their policies and work together for greater goals.

I love the simple village MeshNets we built and the joy seen in kids as they created their own broadcasts for remote villages during COVID isolation. The technology provided affordable, flexible services in remote areas and can do so again in the future, empowering young people to connect, cooperate and contribute. And feel like a part of a local solution; something that someone else’s solution cannot provide.

HEALTH Inc wants to shout out to all the photographers contributing in this article: Padma Gyalpo, Mohd. Imtiaz, Abdul Khaliq, Palzes Angmo, and Rigzin Gurmet.

Another big shout out to Nadia Stuewer and Kathryn Hornbein, editors extraordinaire!

Cynthia Hunt recently retired after thirty-some years of living and working in community development in Ladakh, India.

Moving on from pandemics, she is now interested in helping youth access mental wellbeing information.

HEALTH Inc wants to shout out to all the photographers contributing in this article: Padma Gyalpo, Mohd. Imtiaz, Abdul Khaliq, Palzes Angmo, and Rigzin Gurmet.

Another big shout out to Nadia Stuewer and Kathryn Hornbein, editors extraordinaire!

Cynthia Hunt recently retired after thirty-some years of living and working in community development in Ladakh, India.

Moving on from pandemics, she is now interested in helping youth access mental wellbeing information.

Hockey?

For a health and education organization?

Last year, a young man stopped me in the Leh market. “Jullay Abi-le – Greetings Granny!” After more than thirty years in Ladakh, everyone calls me Granny.

Hockey?

For a health and education organization?

Last year, a young man stopped me in the Leh market. “Jullay Abi-le – Greetings Granny!” After more than thirty years in Ladakh, everyone calls me Granny.

I recognized him from one of our remote villages. When we met, at our first village Winter Camp, he wasn’t doing well in school and I was concerned he would drop out – or worse. Back then, I saw fledgling unhealthy behaviours reflecting his dysfunctional home life, which was filled with substance misuse issues. I even worried he might end up involved in the complicated Indian legal system.

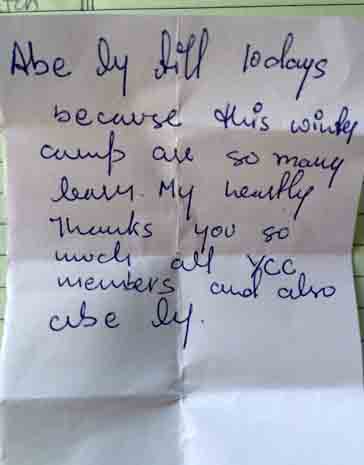

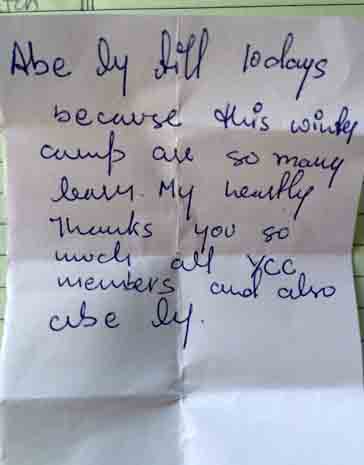

“Abi le – I really want to say thank you.” I demurred, but he stopped me with “No, Abi-le. I want to say thank you. Winter Camp changed my life. It taught me I am someone, I belong somewhere, and I can achieve my dreams.” I listened. I could tell this was important. He described his current life as a professional singer, earning a solid income and being able to care for his family. And passing it forward by volunteering in Camps, helping other young people believe in themselves.

I recognized him from one of our remote villages. When we met, at our first village Winter Camp, he wasn’t doing well in school and I was concerned he would drop out – or worse. Back then, I saw fledgling unhealthy behaviours reflecting his dysfunctional home life, which was filled with substance misuse issues. I even worried he might end up involved in the complicated Indian legal system.

“Abi le – I really want to say thank you.” I demurred, but he stopped me with “No, Abi-le. I want to say thank you. Winter Camp changed my life. It taught me I am someone, I belong somewhere, and I can achieve my dreams.” I listened. I could tell this was important. He described his current life as a professional singer, earning a solid income and being able to care for his family. And passing it forward by volunteering in Camps, helping other young people believe in themselves.

Winter Camp is an ethos as much as it’s a project of HEALTH Inc. Born during one of our annual celebrations of Women’s Cooperatives, where women from 11 remote farming communities gather to celebrate successes and strategize next steps, when the women asked “What good is working for the future without young people? They leave the villages in big numbers. There are no jobs for them. What can we do for the youth?”

Indeed. How do you keep them down on the farm? In spite of large investments in job skills programs, rural-to-urban migration grew exponentially in the 2000’s, with few living-wage jobs for the young in villages. Children were sent away to boarding schools from March ‘til December, making the village feel even emptier, and, honestly, alienating kids from their culture, language, traditions – their ability to sustain rural life.

Sitting on a hill above the village that night, and pondering the women’s questions, I thought, well, I grew up playing pond hockey and it taught me a lot of life lessons. Working in teams. Perseverance, believing in myself, strategic thinking. Asking for help when I fell down. The neighborhood rink brought the community together, while having a place to play made it exciting for kids. Heck, ice hockey is popular in Leh, Ladakh’s capital city, but we have better ice out here the villages. Why not hockey in the villages?

Broaching the subject with Leh administrators, I heard “We already have rinks in Leh. Let those kids come here to learn hockey.” No, no, no – that defeated the goal of using hockey for revitalizing villages – of welcoming kids home to a safe space every winter. Of offering the myriad of rich traditions and learning with on-demand experts, the elders. Of hanging out with friends; cooking, eating, being creative and exploring together. The science of building an affordable, quality sheet of ice – or the art within the wedding ceremony songs. Weaving, herding, local names of animals, or myths from long ago; the things that define who Ladakhis are. I was met with a blank stare. “Let them come here,” he repeated.

Winter Camp is an ethos as much as it’s a project of HEALTH Inc. Born during one of our annual celebrations of Women’s Cooperatives, where women from 11 remote farming communities gather to celebrate successes and strategize next steps, when the women asked “What good is working for the future without young people? They leave the villages in big numbers. There are no jobs for them. What can we do for the youth?”

Indeed. How do you keep them down on the farm? In spite of large investments in job skills programs, rural-to-urban migration grew exponentially in the 2000’s, with few living-wage jobs for the young in villages. Children were sent away to boarding schools from March ‘til December, making the village feel even emptier, and, honestly, alienating kids from their culture, language, traditions – their ability to sustain rural life.

Sitting on a hill above the village that night, and pondering the women’s questions, I thought, well, I grew up playing pond hockey and it taught me a lot of life lessons. Working in teams. Perseverance, believing in myself, strategic thinking. Asking for help when I fell down. The neighborhood rink brought the community together, while having a place to play made it exciting for kids. Heck, ice hockey is popular in Leh, Ladakh’s capital city, but we have better ice out here the villages. Why not hockey in the villages?

Broaching the subject with Leh administrators, I heard “We already have rinks in Leh. Let those kids come here to learn hockey.” No, no, no – that defeated the goal of using hockey for revitalizing villages – of welcoming kids home to a safe space every winter. Of offering the myriad of rich traditions and learning with on-demand experts, the elders. Of hanging out with friends; cooking, eating, being creative and exploring together. The science of building an affordable, quality sheet of ice – or the art within the wedding ceremony songs. Weaving, herding, local names of animals, or myths from long ago; the things that define who Ladakhis are. I was met with a blank stare. “Let them come here,” he repeated.

Not being skilled at accepting “no” for an answer, I mentioned the idea to Canadian friends during a Global Classroom Exchange several months later. No blank stares here; pond hockey devotees, they “got it” instantly. Phone calls and connections made, within a few days we had a 15-minute “audience” with Pierre Boivin, President of the Montreal Canadiens. Ninety minutes later we left with 100 pairs of skates, enough money to bring some coaches over that winter and a plan to share the game – and all the lessons we all learned on the pond – with the Himalayas.

Ron Perowne, of Hockey Without Borders (who equally use hockey as a tool to bring people together), found volunteer coaches, convinced a friend to donate the sticks and helmets to go with the Canadiens’ skates, and sweet-talked 23 bags of gear onto airplanes traveling halfway around the world. Village women leveled a field, shovel-full by shovel-full and kids channeled water from the stream to fill their first rink.

Not being skilled at accepting “no” for an answer, I mentioned the idea to Canadian friends during a Global Classroom Exchange several months later. No blank stares here; pond hockey devotees, they “got it” instantly. Phone calls and connections made, within a few days we had a 15-minute “audience” with Pierre Boivin, President of the Montreal Canadiens. Ninety minutes later we left with 100 pairs of skates, enough money to bring some coaches over that winter and a plan to share the game – and all the lessons we all learned on the pond – with the Himalayas.

Ron Perowne, of Hockey Without Borders (who equally use hockey as a tool to bring people together), found volunteer coaches, convinced a friend to donate the sticks and helmets to go with the Canadiens’ skates, and sweet-talked 23 bags of gear onto airplanes traveling halfway around the world. Village women leveled a field, shovel-full by shovel-full and kids channeled water from the stream to fill their first rink.

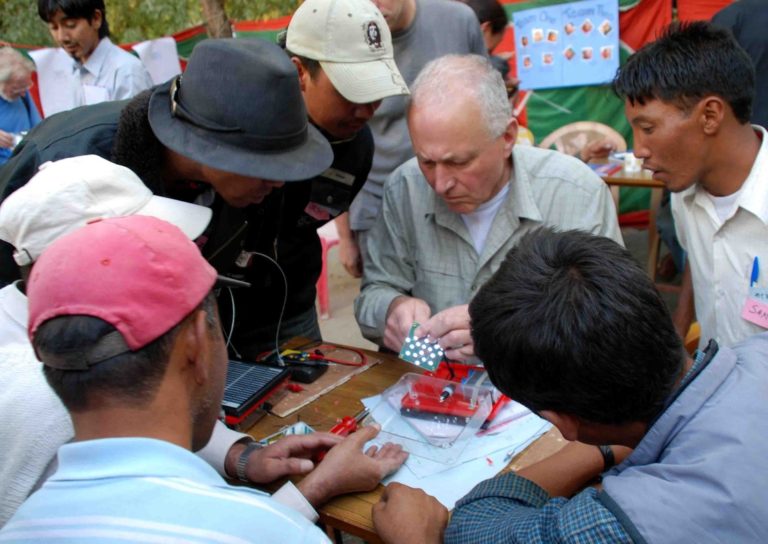

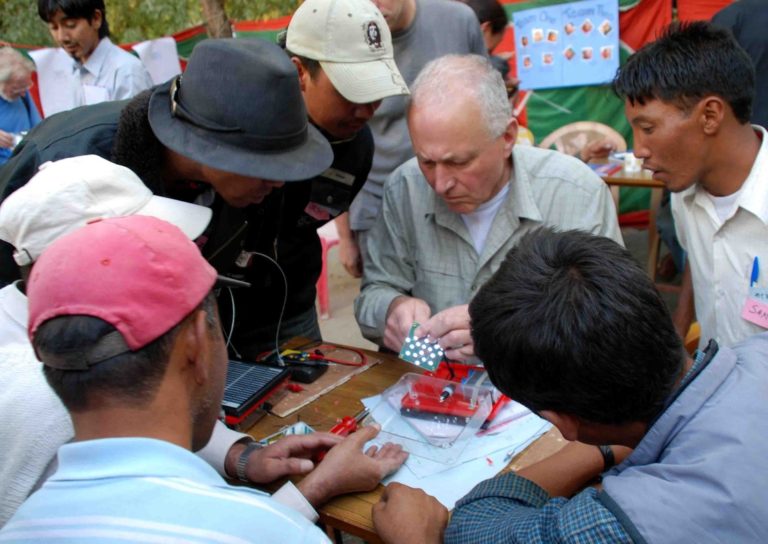

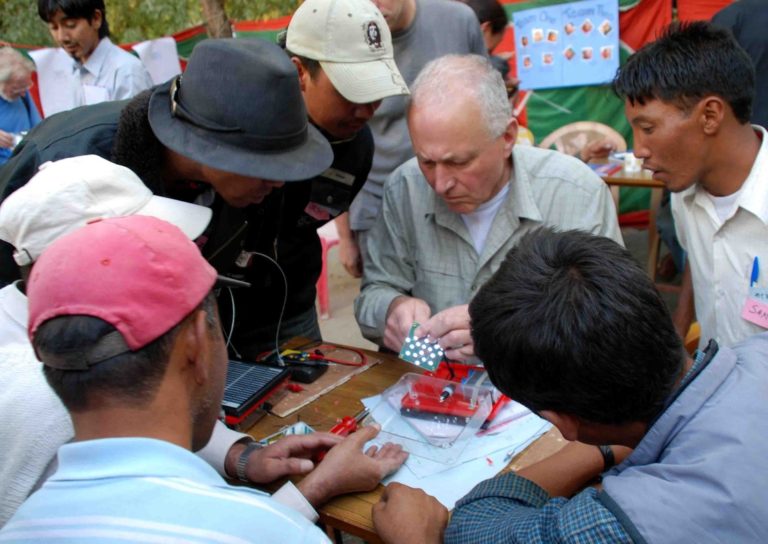

Eighty kids and youth showed up for the fun that winter. Skating in the morning, and, when the sun softened the ice, gathering at the community school with a goal of learning how to learn. Rather than memorizing textbooks, we discussed village issues, tested ideas, and designed solutions for real-life challenges like insulating water barrels or generating electricity from water wheels. And when design number one failed; the skill of iterate, iterate and iterate again. At night, we cooked together, created contraptions to resurface the rink (best DIY Zambonis in the world), sang, danced and in just 30 days, every young person felt in his or her bones the joy of belonging to this place.

Their self-image changed from feeling less-than to “I am” and “We can”. After all, who ever heard of leveling a mountain and building a hockey rink?

Eighty kids and youth showed up for the fun that winter. Skating in the morning, and, when the sun softened the ice, gathering at the community school with a goal of learning how to learn. Rather than memorizing textbooks, we discussed village issues, tested ideas, and designed solutions for real-life challenges like insulating water barrels or generating electricity from water wheels. And when design number one failed; the skill of iterate, iterate and iterate again. At night, we cooked together, created contraptions to resurface the rink (best DIY Zambonis in the world), sang, danced and in just 30 days, every young person felt in his or her bones the joy of belonging to this place.

Their self-image changed from feeling less-than to “I am” and “We can”. After all, who ever heard of leveling a mountain and building a hockey rink?

Since 2006, Winter Camp has been one of our most successful programs, and the ethos underlying camp grew. We made it a democratic community, with kids setting the schedule, the goals, and deciding who’s working when and why. Skills in negotiation grew. Parents came to understand that inquiry-based learning held value for their children’s future. And Youth Associations (local mentors operating camps) built leadership capacity in leaps and bounds. We scaled the concept from farming villages, to herding communities, to agencies like the District Police (camps for at-risk youth!) and NGOs serving the differently-abled community,

As challenges evolved, so did we. A rise in substance use taught us to offer alternatives for dealing with underlying pain and building mental wellness – ideas gleaned from Canadian partner organizations. As the climate changed, we discussed resilience in a time of unknowns. And as competitive hockey grew across Ladakh, we ensured there remained room for everyone to skate – holding plenty of space for kids who didn’t care about being great skaters on a national team, but who simply loved play. Who loved feeling a part of. And who loved setting personal goals and achieving them.

Since 2006, Winter Camp has been one of our most successful programs, and the ethos underlying camp grew. We made it a democratic community, with kids setting the schedule, the goals, and deciding who’s working when and why. Skills in negotiation grew. Parents came to understand that inquiry-based learning held value for their children’s future. And Youth Associations (local mentors operating camps) built leadership capacity in leaps and bounds. We scaled the concept from farming villages, to herding communities, to agencies like the District Police (camps for at-risk youth!) and NGOs serving the differently-abled community,

As challenges evolved, so did we. A rise in substance use taught us to offer alternatives for dealing with underlying pain and building mental wellness – ideas gleaned from Canadian partner organizations. As the climate changed, we discussed resilience in a time of unknowns. And as competitive hockey grew across Ladakh, we ensured there remained room for everyone to skate – holding plenty of space for kids who didn’t care about being great skaters on a national team, but who simply loved play. Who loved feeling a part of. And who loved setting personal goals and achieving them.

Twenty-one villages and groups have gone through the Winter Camp program. Thousands of kids experiencing winters filled with healthy development at the individual and community levels. Youth living as leaders in their villages (and beyond), passing lessons forward. North American pond hockey aficionados ensuring the program continues to grow and thrive. And young people stopping me in the market, saying “Jullay Abi-le, thank you for Winter Camp.”

Taking a step away from the rink for just a second, there is a Goethe quote I carry in heart and head that supports Camp design:

“Whatever you can do, or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power and magic in it.”

Because there is magic on a village rink. And genius in using what kids love to help them believe in themselves. And there is power in kids who believe.

Twenty-one villages and groups have gone through the Winter Camp program. Thousands of kids experiencing winters filled with healthy development at the individual and community levels. Youth living as leaders in their villages (and beyond), passing lessons forward. North American pond hockey aficionados ensuring the program continues to grow and thrive. And young people stopping me in the market, saying “Jullay Abi-le, thank you for Winter Camp.”

Taking a step away from the rink for just a second, there is a Goethe quote I carry in heart and head that supports Camp design:

“Whatever you can do, or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power and magic in it.”

Because there is magic on a village rink. And genius in using what kids love to help them believe in themselves. And there is power in kids who believe.

HEALTH Inc wants to shout out to all the photographers contributing in this article: Nicole Lundstead, Andreas Bruhn, Nick Zacoi, Lucie Edwards, Tom Roach, Andrew Roehr, Jim Stone and HEALTH Inc staff. Another big shout out to Nadia Stuewer, editor extraordinaire!

Cynthia Hunt recently retired after thirty-some years of living and working in community development in Ladakh, India.

The Goethe quote is from The West Ridge by Tom Hornbein, which Cynthia read some forty years ago. Good read if you’re looking for one.

Lighting Ladakh